Udaipur: Extraordinary Care

Text by Niharika Awasthi

Photographs by Chris Hnin

“Several years into my practice as a physician at my own private clinic, my father was diagnosed with a chronic illness. I could not afford the treatment or the medicines. I had a hard time coping with the rising cost. So, hoping that government subsidies will be able to help my situation, I applied to join the public health sector. The whole ordeal really made me reflect on my role as a doctor, and the patients I should really be serving,” recalled Dr. Rajesh Bharadiya.

During a visit to Maharana Bhupal Hospital, Dr. Dr. Rajesh Bharadiya stops to check in with Dr. Sanjeev and the pharmacist on duty.

Dr. Bharadiya is the officer in charge at the District Drug Warehouse (DDW) in Badi, Udaipur. He oversees the flag-bearer, or model, DDW branch of Rajasthan’s Free Medicine Scheme in the region. For the last five years, he and his team have been making sure that the benefits of the Free Medicine Scheme fully reach the people of Udaipur. The DDW is located about fifteen kilometers outside the main city of Udaipur.

Udaipur, the city of lakes, is a major city of Rajasthan, founded by and named after Maharana Udai Singh II as the new capital of Mewar. The city spreads out over an area of 37 square kilometers in the southern part of Rajasthan. It sits in the midst of the Aravalli hills and is laced with beautiful lakes. While a popular tourist destination, it has been making headlines within Rajasthan for its ability to provide its people with access to free health care.

Dr. Rajesh Bharadiya is one of the thousands of medical professionals involved in making the Mukyamatri Nishulk Dava Yojana (MNDY), or Free Medicine Scheme, in Rajasthan operate. MNDY, launched in October 2011, provides free, generic medicines to all of its population, especially those in extreme poverty and those struggling with ill health. To implement this program, Udaipur relies on 240 doctors, 122 nurses, 916 Auxiliary Nurse Midwives (ANM), and 2,381 Accredited Social Heath Activists (ASHA).

In 2012, Team Udaipur was recognized as the top performer in Rajasthan for its successful implementation of MNDY. Its performance can be credited to several factors: dedicated staff and effective communication

between the District Project Coordinator and the field staff.

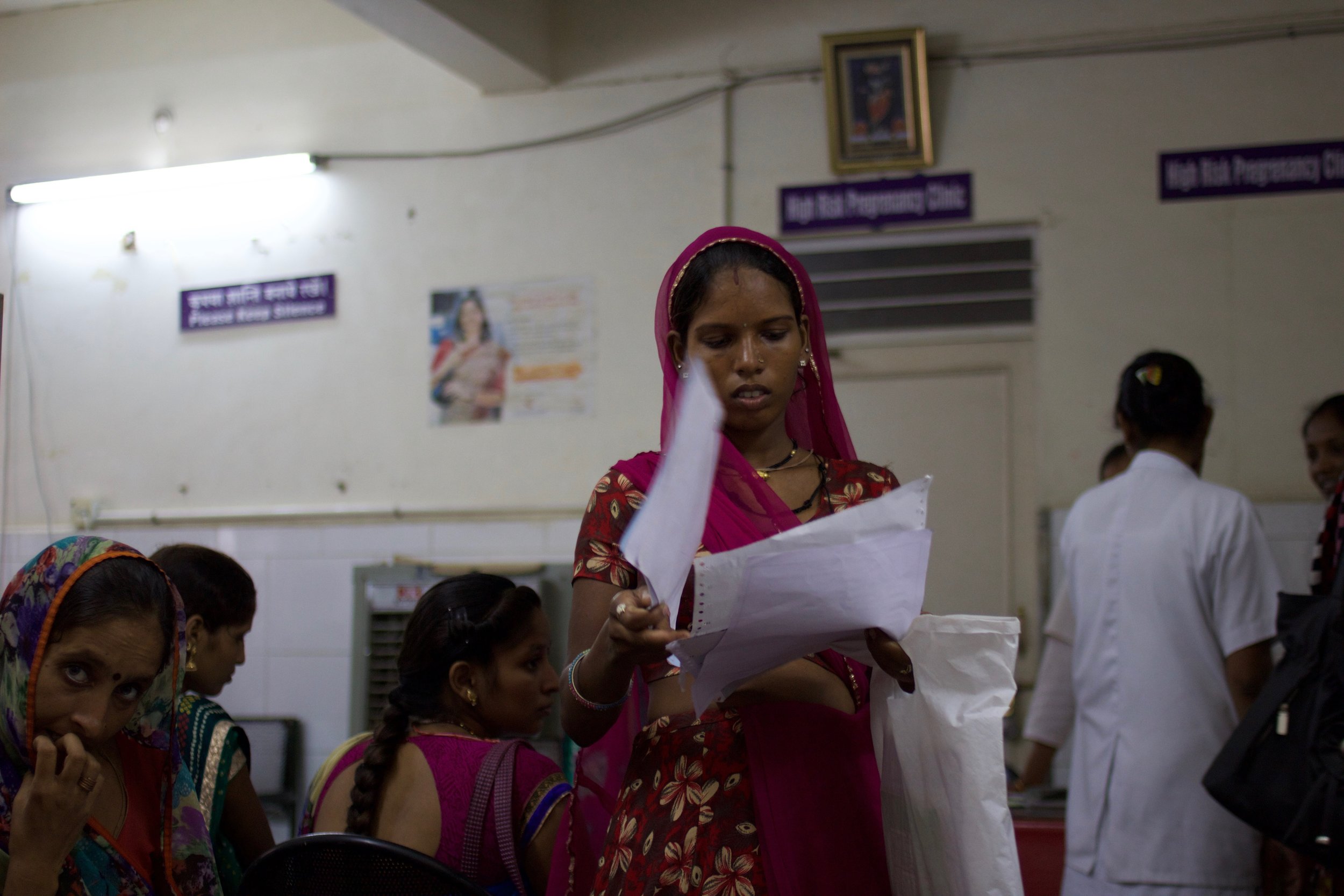

Pregnant patients who have come to Zanana Public Hospital for their regular check-up listen attentively for further instructions from the nursing staff.

To have the Free Medicine Scheme operate as effectively as it has, there were a number of challenges to overcome, including doctors’ preferences for branded medicines along with their relationships with the pharmaceutical companies – a challenge medical societies face globally.

While the Scheme was still incubating, it witnessed significant resistance from doctors, who had doubts that this ambitious Scheme would work; many saw it as a waste of public funds. It has been almost five years since the Scheme has been functional; now the tables have turned and the doctors are at the front lines of implementation and execution. Long queues of patients at Drug Distribution Counters in government hospitals and vacant private medical stores with idle pharmacists sitting at the counters across Udaipur are two of the most visible impacts of the success of the scheme.

This would have not been possible without committed health workers on the ground, the front line of the scheme, such as ASHAs and ANMs. ASHAs are the trained, female community health activists who are often the interface between the community and the public health system. They mobilize people in the villages to engage in healthy life practices. ANMs are appointed by the government to help communities achieve the targets of national health programs. They work at Primary Health Centers and Community Health Centers.

ANM Usha Goel’s job is to tell people about various health programs and the government Scheme. She says, “MNDY has been able to bridge the trust deficit between health workers and the community. Initially, when we used to tell them about some schemes, they wouldn’t trust them. But after MNDY and its considerable success, people have started showing faith in them. For pregnant women, the Scheme is very helpful. We make sure that they visit health centers at regular intervals and avail free medicines and checkups at the health centers.”

In India, between 1995 and 2014, public expenditure on heath care saw a minuscule rise from 1.1 percent to 1.4 percent. India continues to rank low in social development indicators because people are dying due to a dearth of quality health care.

“Medical students cannot be taught about all public heath care schemes, thus when resident doctors start practicing at the Medical College, they are given a sensitization program on the functioning of MNDY and the importance of making free and quality health care available to its people,” says Dr. Sanjeev Kumar Tak, Chief Medical and Health Officer, Udaipur. In the sensitization program, resident doctors are also exposed to the social conditions in which they will be working.

New doctors and residents are introduced to the Scheme’s mechanics as well as its purpose and goals. Because medicines are most often prescribed by resident doctors in the medical college hospitals, it is important that they are well informed about both the Free Medicine Scheme and about prescribing generic, non-branded medicines. It is an effort to counter the bias that non-branded drugs are of poor quality or less effective than their branded counterparts.

A young resident doctor, Dr. Mahesh, at MB Medical College said, “Initially, when I joined I did not know the

importance and the need for the Scheme. In college, we were so engrossed in studies and badly wanted to succeed in life and make money. But when I started practicing here at the medical college, I was moved by the poverty of the patients. People in torn clothes with feeble bodies made me realize in life, success is just not being at the top, but serving the poor and helpless. I do not prescribe branded medicines to the poor. I always make sure prescriptions that I write for my patients have generic medicine’s name, signed under my name.”

Aju Devi, working at Community Health Center Khewada, said, “As an ASHA worker, our job is to travel door to door in a community and find people who need medication. If we have some medicines available, I can give then to them. Had it not been for MNDY, we wouldn’t have able to give them free medicines.”

Contributing to this success is a strong monitoring system, coupled with supportive supervision. The coordinator and managers are able to provide and receive regular feedback to and from the field. For checks and balances, they hold monthly review meetings with doctors, ANMs and ASHAs. Udaipur has also developed a feedback app for the patients.

The emphasis is on the care of the patients, which is spread from the top of the Scheme – Dr. Bharadiya – to those working door to door in the communities. Dr. Sameet Tak from the Maharana Bhupal Medical College, said, “In cases of emergency, we send medicines without doing paper work. We believe service comes first. If someone does not want to work, one can quote any rule and get way with the work. We make sure rules do not come in between care and the patients in our service. Also we do not keep phones on silent, so that we do not miss a call from somebody who really needs us.”

Last year, Dr. Bharadiya’s son acquired dengue fever. His situation was critical and everyone (friends, relatives, and his colleagues in the hospital) recommended that he take him to a private hospital in one of the big cities. However, Dr. Rajesh Bharadiya’s faith in the public health care system remained unshaken. “I wanted my son to get

treated in the public hospital only; his platelets were 9,000, far less than required in the patient suffering from dengue. Time and again, people would tell me that I was expecting too much from the system and might have to pay a price for it. But somewhere in my heart I knew my son would be all right. At last when he was cured, my faith in the public health care system was restored. I have tried setting an example for others to please trust the public health care system.”

Sitting in one of the meetings at the Medical College, Dr. Tak mentions the Hippocratic Oath. This Oath is the rite that physicians across several countries take before they enter the profession; it is a code of ethics that they need to abide by while serving that emphasizes “do no harm”. “Through the Free Medicine Scheme, this is what we are doing. The average Indian cannot afford to visit a private clinic.”

An elderly patient, suffering from hypertension, gets her monthly dose of medicine for free under the MNDY scheme.

Kherwara is an 80km drive from Udaipur. The region is dotted with terrace farms and wide spaces between houses in the Aravalli hills. Agriculture and self employment are the main occupations of the residents of this region. With improved infrastructure and the extension of the National Highway System, the Primary Health Center in the area receives a lot of cases of accidents and injuries. The highway has meant an increase in roadside hotels which has lead to more people involved in the sex trade, resulting in a rise in HIV infection and STDs. The region faces an acute shortage of doctors and other medical staff. Many doctors are reluctant to work in this poorer region, seeing less opportunities for personal and professional growth. Yet, there are those who are serving the poorest of the poor.

Dr. Arun Meena, a medical officer at the Primary Health Center Sulai, said that the tribal patients in the region often visited faith healers rather than the medical centers to receive their diagnosis and medication. He said that some considered illness to be an act of god. But now they know that they can get free medicine, bringing them to the hospitals. They are especially seeing an increase in women coming to the health care centers. Radio programs, ASHAs, ANMs and public advertisement have helped to disseminate the information about MNDY and to create awareness. This Scheme has not only worked as a free medicine provider, but it has brought about a change in the attitudes and thinking of the community as well.

“Once, a faith healer arrived at the community health center as a patient suffering from diarrhea. He heard about the hospital through one of his patients who recommended that he see a doctor if he was unable to cure himself through his healing tactics.” said Dr. Meena.

Dr. Meena said that he is originally from a tribal community, and he has seen his community caught in the web of blind faith and suffering due to a lack of awareness. He said, “Twenty five years ago, people did not go to see the doctors and did not even have access to basic health care. Free medicine has helped the community get rid of the regressive custom of faith healing to a great extent.”

As a medical officer, Dr. Meena’s job is not just to treat patients and give them medicines. He sees himself in a greater role as a doctor. He always asks his patients about their backgrounds, which community they belong to, and how their community is aware of the free medicine scheme. He ends his conversations saying, “Medicines are effective in the short run, but awareness of health options will help well into the future.”

Within the scheme, the smaller Primary Health Centers offer another layer of health care provision. Dr. Lakshita Jain, the Medical Officer in charge at the Primary Health Center in Khandi Ovari, said, “I joined the service in December 2011. MNDY was launched in October 2011. The word had not spread of what the Scheme was yet, and there were frequently open appointments. However, gradually people started coming to the centers. People were initially reluctant, thinking that beyond visiting the hospital they would have to travel a greater distance still to get their medicines. Now that the medicines are available at the hospital’s doorstep, patients are lining up to visit the clinics. Within three to four months of my posting, there was a tenfold increase in daily patients; from 10-20 to 100. This has been especially beneficial for children and mothers.”

A mother and daughter duo waits anxiously for the onset of labor contractions at a Primary Health Center along the Udaipur-Ahmedabad highway.

Many women in modern India remain in veils and so does their health care. They are the least likely to visit hospitals and the most likely to die without accessing proper care. Women carry the burden of patriarchy on their bodies. The Free Medicine Scheme has proved to be a boon for women in Udaipur. Women who did not come to hospitals, fearing their health care would cost a fortune to their families, now confidently enter the premises of the hospitals. One of the satellite hospitals in Udaipur has a separate Drug Distribution Counter (DDC) dedicated to women to make it more convenient for women to get their prescriptions.

“I have come to get my delivery done ,“ says Shabana at a labor ward in Janana Hospital. She was there to deliver her second child. “I am content with the facilities and free medicines they provide at the hospital. Seven years ago when I delivered my first child, things were not as easy as they are now. We had to be on our toes if we wanted services from hospitals, but now medicines and services are accessible in the public hospitals.”

Some doctors in Udaipur provide free consultations at their homes as well, during evening hours and on Sundays. They do it because they want to serve as many patients as they can. The long line of waiting patients at Dr. Bharadiya’s free clinic at his old residence says a lot about how patients trust him. According to his patients, he has been at the same clinic around the same time for the last thirty years without frustration or fatigue. Dr. Dr. Rajesh Bharadiya works with minimum resources. He has a hand bell that he rings to indicate patients’ turns, and his prescription pad is made of old calendars.

A woman who works as a sweeper arrives at the clinic. In her mid-50’s, her face is pale and her body looks tired. She is here to get a prescription for her backache caused by carrying her cart on her back. Another woman is there to get medicine prescribed by the doctor for her husband who works in Kuwait. For his free clinic, Dr. Rajesh Bharadiya sent a proposal to the government asking to be allowed to have generic drugs to distribute to his patients so they do not have to go to the private medical stores. He has not succeeded in this effort as yet.

The same zeal is found in Dr. Renu Khamesra, who is a Neurology Specialist at Maharana Bhupan Hospital. She runs a free clinic at her home on Sundays from 5:30am to 6:00pm. Dr. Khamesra is a cancer survivor, and she understands the helplessness of a human being who is struggling. She said, “My own suffering made me more empathetic towards the suffering of others.”

When asked whether the Free Medicine Scheme has increased the workload for doctors, Dr. Radha Rastogi, a professor in the Gynecology Department at Mahrana Bhuwan Medical College, laughed and said, “Yes, the workload has increased as patients have increased at OPD [Out Patient Department]. But this has also made

things less hectic for us in the sense that we need not go to people again and again to tell them about schemes. People come here and, along with medicines, they get to know about various schemes, which help us in achieving the targets.”

The Free Medicine Scheme has brought lot of positive aspects to the lives of doctors, but at the same time it has posed challenges for them, as there is a shortage of doctors in health centers across Rajasthan. Dr. Rastogi summed up the challenges a doctor faces with the success of the Free Medicine Scheme in Udaipur, “Patients

have started coming to hospitals in enormous numbers, and we are still not able to meet the standards of doctor-patient ratio at our hospitals.”

She is disheartened by the fact that people come to hospitals with an expectation of 100 percent results. “People think doctors are god, but at the end of the day, we are doctors. We try our level best to give the best services.”

“Weekend breaks,” she said “are necessary to maintain personal health, as throughout the week we deal with lots of pressure and depressing stories of patients. To be able to counsel patients better, the well being of a doctor is very necessary.”

Patients wait in line for their consultation with a general physician at Satellite Hospital Hiran Magri Sector 6.

As the evening falls and the sun sets in the sky, Dr. Rajesh Bharadiya moves towards his motorbike with a brown bag in one hand and his helmet in another, readying for his drive from home to his clinic. Passing one of Udaipur’s larger lakes, he said, “I was here with my wife when we just had our first child. Ever since then, I have just passed by Fateh Sagar Lake but did not stop to cherish the view. My family often complains that I am not able to give time to them, but I have told them as a doctor I cannot afford to enjoy life at the peril of my patients.”