Jaipur: The Role of Civil Society

Text by Pooja Sivaraman

Photographs by Abhinav Sharma

There are certain professions that can serve as recipes for cynicism. Though Dr. Narendra Gupta has collected many of its ingredients, practicality and rationality are what occupy his reflections on the Indian health care system. His life simultaneously chronicles the uphill battle for the right to health in India as well as the changing political climate of a post-partition nation. Sitting in his living room during a rainstorm in his hometown of Chittorgarh in Rajasthan, the 63-year-old doctor calmly asks his wife for a cup of chai and begins to talk.

The movement for free medicine in Rajasthan began its stirrings in 2007 through initial advocacy by civil society groups, doctors, and public health experts. Alongside Dr. Samit Sharma, considered the father of the Rajasthan Free Medicine Scheme, Dr. Gupta was integral in its conceptualization and in leading this movement as one of the founders of the non-governmental organization Prayas.

Born in 1953, shortly after the end of British colonial rule, he witnessed the rise of India’s now booming private health care system. The country’s mixed economy served as a catalyst for the “reverse Robin Hood” of patients, where the rise of the sector became increasingly expensive to the point where out of pocket expenses, as a percentage of household expenditures, were some of the highest in the world. The cost of healthcare in

passing years proved to become the largest financial force pushing people below the poverty line.

Though Dr. Gupta’s work lies at the heart of medicine and social justice, his heart appears to be governed by the latter. During his schooling in the urban city of Ajmer, about 120 kilometers south of Rajasthan’s state capital of Jaipur, he was never particularly interested in medicine. “I got better marks in biology,” he laughed, and that was that in deciding his career path. However, during the 1970s while he was in medical school, he became very involved in his student government.

“I became exposed to a lot of different politics” he explained, “and until then I was not aware of social issues.” This also coincided with a period of major political upheaval in India. During the state of emergency declared by Prime Minister Indira Gandhi from 1975 to 1977 — a period of rampant forced sterilizations, curtailment of civil liberties, and extreme censorship of the media – Dr. Gupta became the General Secretary of his college.

Graduating with a Bachelors of Medicine in 1977, Dr. Gupta began his career in India’s capital, New Delhi. Though the Emergency was winding down then, the government under Prime Minister Morarji Desai crumbled in two short years, leaving Indira Gandhi to regain power in 1980. The events of these two years gave rise to a skeptical populace, critical of how they were being governed. From a medical standpoint, Dr. Gupta felt as though there were too many barriers between the people and the public health system. “My job was not to be a link between the medical services and the people,” he said, “I should be helping people become more aware of their health issues.” This, among other sentiments, prompted him to leave New Delhi.

“The question Dr. Gupta poses is why is the Indian health care system benefiting the rich and burdening the poor? ”

One of his classmates from medical school invited Gupta to join a voluntary organization working in the rural areas of Uttar Pradesh. “This really excited me,” he exclaimed, “I was not exposed to this angle very much” – this angle being politically-minded medicine. Dr. Gupta became aware of community and public health issues, particularly the importance of preventive care. He had the opportunity to speak to doctors who were setting up community health centers and making basic healthcare accessible to people below the poverty line. These initial centers became the groundwork for the ASHA (Accredited Social Health Activist) mission launched in 2005.

Dr. Gupta began to feel a sense of duty toward his home state. After consulting several New Delhi-based anthropologists, he decided to continue his work in a rural town in the Rajsamand district of Rajasthan – Devgarh – where he spent the following ten years of his life. “Generally, doctors want to move from a small place to a bigger place and so on,” he said, “but I was going in the reverse direction.”

“65 percent of people in India lack access to essential medicines”

Sitting on a hilltop in a wooded region of the state, Devgarh had no electricity or running water when he arrived. Despite having been once the capital of Rajasthan prior to British rule, it was now very isolated. “This work really excited me, I had to find a way to do this kind of work but still stay alive,” he laughed. “I could not charge the people who I would work with, they would not have any money to support me.” The only place to live was an historical, but highly dilapidated, castle that had been the home of pre-colonial royalty. The castle contained a small but restored room that Dr. Gupta came to call home.

In tribal areas, the most common ailments were infectious diseases that did not require hospitalization, such as malaria, diarrhea, scorpion bites, and viral fevers. “The prevalent infections are self-limiting,” Dr. Gupta explained. “Diarrhea and pneumonia will either persist until the person dies, or they will get solved within five to seven days.” Where healthcare was inaccessible, many people would resort to home remedies, visit faith healers or seek the assistance of unofficial doctors, commonly referred to as “Bengali doctors” by the medical community.

There is a joke often told of a doctor claiming he was so special, he could make a patient forget about their ailment in a matter of seconds. How? Well, one day a man came in with a terrible migraine. The doctor reached into his desk, pulled out a metal hammer, and with one swift movement he slammed it down onto the patient’s foot. The man cried out and immediately started clutching his swollen foot in pain. “See?” the doctor chuckled, “you’re not thinking about your head anymore, are you?”.

This tale is an analogy Dr. Gupta used to portray the shortcomings of the Indian healthcare system. The “reverse Robin Hood” caused by the privatization of healthcare applies specifically to rural areas. Since common ailments in villages are often treated by antibiotics, unofficial doctors learned to be successful within these communities by administering antibiotic shots. However, with no official medical training, patients are often wrongly diagnosed or given incorrect advice. People with diarrhea are told to eat and drink less, when in fact serious diarrhea necessitates the exact opposite. “Lots of health education was needed,” said Dr. Gupta, “but that had to be done in a very friendly, one-to-one manner.”

One of the largest barriers, according to many in the professional health community, to regulating healthcare is the prevalence of faith healers in tribal and rural villages. With the lack of accessible healthcare facilities, traditional faith healers remain an important resource for villagers. Through the use of exorcisms and other unconventional methods, faith healers are often seen as a hindrance to the adoption of western medicine practices. Medical practices that are heavily grounded in one’s faith are often difficult to invalidate. One of the challenges for the medical community over the year is finding a way to build trust and understanding within these communities.

During Dr. Gupta’s time in Devgarh, a faith healer became sick. For a long time, the healer did not seek any medical treatment, and his condition worsened. “When I got to know about it, I went to see him and gave him medicine,” said Dr. Gupta, “I then began to convince him about my practice.”

Instead of lecturing him on the benefits of western medicine, Dr. Gupta suggested the healer advise his patients to seek medication from a hospital in addition to his ritualistic methods. Though it was a challenging task, the faith healer soon realized the benefit of such a system. If a patient is given one sugar pill and one antibiotic pill every day for a week, one will not be able to deduce which pill was the cure. However, if the patient is cured, neither method will be questioned. With similar logic, Dr. Gupta convinced the community of faith healers in Devgarh that a secondary treatment at a hospital would create a better cycle of trust for their treatments. The faith healers’ prescriptions came to include a trip to a health care center.

This is a success story among many defeats over the years. Though some of the inadequacies of the healthcare system are due to misleading language or lack of regulation, there are also blatant instances of exploitation. Dr. Gupta began to tell a story of a young tribal man who became seriously ill. “Though I didn’t have good facilities for keeping the patient overnight, I took him in and put him on an intravenous drip,” he recounted. “Early in the morning, someone turned up from the town and said, ‘Look, I am his sahukar (money lender). Please treat him well, whatever the expenses are; I will take care of them. You should do everything that you can, even if it is very expensive’.”

Dr. Gupta came to learn that many of the patients he treated were often heavily in debt. “I couldn’t understand this man’s motivation for giving money to someone he barely knew,” he said. He learned that money lenders feed off of vulnerable patients in times of need, and later claim exorbitant amounts of interest. “The relationships between the moneylenders and the people are very interesting,” said Gupta, “it is a patronage cum exploitation.” As health care costs rose, more and more poor found themselves in debt or unable to access medical services.

Dr. Gupta also does not excuse the government from exploiting its poor. “People from the forest department would come to people’s home and take chickens or hard liquor [for no valid reason],” he elaborated, “They’d sometimes abuse them.”

In 1982, Dr. Gupta began to work in a mini-PHC (primary health center), a government health care facility. This was also around the time when he became heavily involved in social activism. He developed a dedication towards educating the tribal communities on the ways in which they were being exploited by the government.

“The government became very wary of us,” he said, “They said we are spreading communism and should not be given power over the centers.” Dr. Gupta began to operate education centers that mobilized the public to fight for the right to their own land. This made his medical work at the mini-PHC very challenging. “[The government] stopped giving us money until we ran into financial problems,” he said, “Then we had to file a public interest litigation in the high court.” Though they won their case, the team of Dr. Gupta’s doctors decided to forego their control over the mini-PHC to focus on community health advocacy.

Another area of concern for Dr. Gupta, one that made him leave New Delhi and turn to his current work, was the sterilization campaign initiated by Sanjay Gandhi, Indira Gandhi’s son, during the emergency in 1977. It was a campaign for compulsory sterilization to control India’s population growth. Monetary benefits were given to people who underwent vasectomies or hysterectomies. Despite the fact that the sterilization process for females is a far more complicated process (not to mention riskier), the campaign was primarily focused on women. Eventually the program was repudiated, but not before it instigated thousands of forced hysterectomies, particularly in poorer or rural areas where private institutions could coerce women into the procedure. The governments succeeding Indira Gandhi inherited the burden of rectifying the consequences of this campaign.

“It was a very easy way for doctors to make money,” explained Dr. Gupta, “and a relatively easy operation.” The hysterectomies were a byproduct of the increasing number of private healthcare institutions, which continue to be unregulated in rural areas. “Women and men in tribal areas became sexually active at a very young age,” said Dr. Gupta. “There were many cases of sexually transmitted infections or reproductive tract infections [in the villages]”.

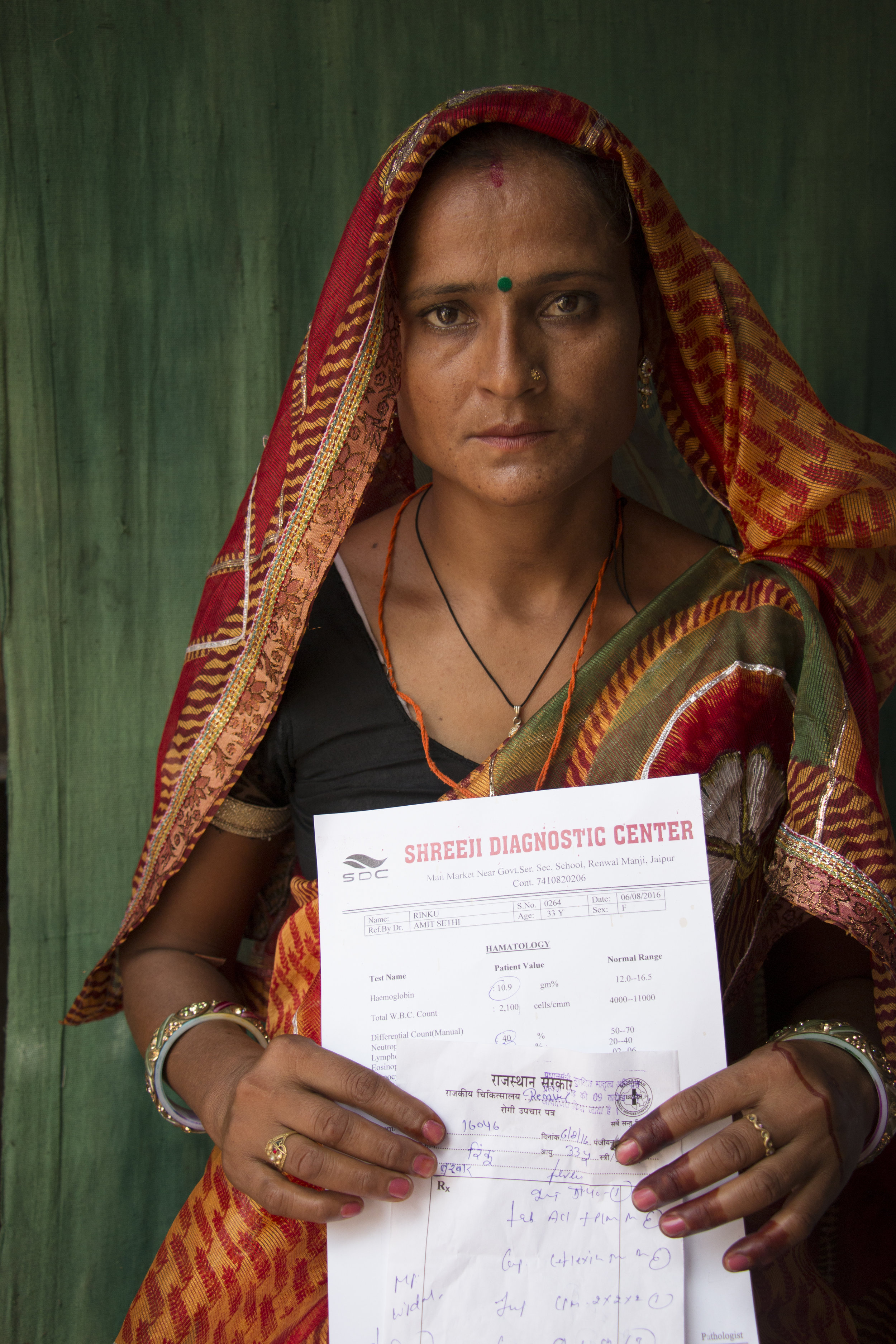

In response to the most basic reproductive ailments, doctors would advise female patients to remove their uteruses, often emphasizing the immediacy of the procedure so no further tests could be administered. “In the west, most hysterectomies are done in post-menopausal women,” said Dr. Gupta, “But in India, the average age for women [who undergo this operation] is 30-32 years.” The procedure, which often takes place in unsanitary conditions, can cost between eight to twenty thousand rupees ($120-300). “Quite a lot of women felt cheated after the hysterectomies were done,” said Gupta, and many were forced into debt as a result of the unnecessary surgery.

The question Dr. Gupta poses is why is the Indian health care system benefiting the rich and burdening the poor? The issues limiting access to health care are rooted in a lack of money and/or a lack of information. Poor people are being cheated out of money they do not have, and in the process are denied their basic right to healthcare. “The spending on healthcare needs to triple,” said Gupta.

Prayas is “a grassroots public interest advocacy group, that has been mobilizing community actions for universal access to health care as an entitlement since 1979.” In 1998, Dr. Gupta opened the Prayas office in Chittorgarh–the primary testing grounds for the Rajasthan Free Medicine Scheme.

In 2007, he began to work very closely with Dr. Sharma to instigate a scheme that would supply generic drugs at cheaper prices. The generic drugs would sell at a 20 percent markup, substantially lower than the markup administered by private pharmaceutical companies. “At first I thought to sell medicine at a slightly higher

price so people learn the value of the medicine,” said Dr. Gupta, “But then I realized one can easily explain that they are already paying for it with their taxes: it’s not free of cost.”

In 2009, Chittorgarh tested the possibility of the free medicine scheme by implementing its own program. According to The World Medicine Situation Report of 2011, 65 percent of people in India lack access to essential medicines. Prayas stated that India ranks 42nd in out of pocket health spending; 3.4 percent of the rural population and 2.8 percent of the urban population slide into poverty annually as a result of health care expenses.

About 40% of hospitalized patients have to borrow money even after selling assets for health expenses. In a study conducted by Prayas in 2011 in Rajasthan, showed that more than 60 percent of out of pocket spending for health care is on medicines. Prayas argued that this “is a catastrophic amount for the large majority whose daily income is not beyond US $2 a day.”

On October 2nd, 2011, the Mukhyamantri Nishulk Dava Yojana (the Chief Minister’s Free Medicine Scheme) came to fruition.

“I couldn’t even imagine the rush,” exclaimed Dr. Sharma (not related to Samit Sharma), a doctor in a government hospital. “The whole room was blocked by patients.” Dr. Sharma was the only doctor in the ward the night the free scheme commenced. She described seeing 500 to 600 patients within two hours of the scheme’s initiation.

“People thought it was a very good scheme,” she said, “They thought it was so good that it would not last long, so they would come to collect enough medicine for the future.” She explained how her patients, who never had much faith in the government, were in disbelief.

Though the Free Medicine Scheme has proven to be widely beneficial, it is certainly not a Band-Aid solution to Rajasthan’s healthcare problem. That being said, the Free Medicine Scheme is the first step to ensuring that healthcare is not a privilege, but a basic human right.